November 14, 2023

While the mishandling of missing person cases has been an ongoing problem for Chicago police, there is momentum — both at the state, city and community level — for real change.

The Illinois Task Force on Missing and Murdered Chicago Women convened for the first time May 25, 2023. It has a sprawling scope that includes examining policies and institutions like police and child welfare programs, improving data collection and analysis, and providing support for impacted people, families and communities. This body aims to ultimately reduce violence against Chicago women and girls by zooming into the root causes and current response mechanisms. “We’re just looking for information and patterns [to] see if we can put together a profile and save lives,” says state Sen. Mattie Hunter, who sponsored the law to create the group.

The task force hopes to identify underlying issues driving missing and murdered women cases by using data from city, county and state agencies. But, crucially, as seen in this investigation, Chicago Police Department data is deeply flawed. Hunter and state Rep. Kam Buckner, who created the task force, were hopeful that data would shed light on the issue.

Despite the poor quality of the data, it presents a unique opportunity for the task force to use data analysis and strategies used by task forces that have gone before them. For example, they can crossmatch names of missing people with people who have been found deceased, to inform their discussions around violence prevention.

While the task force cannot enforce its own recommendations, which will be shared with the Illinois General Assembly and Gov. J.B. Pritzker by the end of 2024 (and on a yearly basis after), these recommendations could be the basis of future legislation. “All we can do is put information into legislation requiring [the Chicago Police Department] to do this and requiring them to do that,” Hunter says. Ultimately, enforcement would fall to the Illinois Attorney General’s office, says Hunter.

For instance, Illinois legislation that went into effect in 1984 says that law enforcement agencies should improve their data collection on missing person cases for children in order to provide better statistics on the issue.

Buckner has high hopes for the task force’s impact on improving public services for families, but he notes the state has a limited role to play.

“Because Chicago is a ‘home rule’ municipality, the state’s authority over CPD is limited, but the City Council has authority and the mayor’s office does,” says Buckner. “If there are instances where it is documented that CPD is not following the law, there is absolutely recourse at the city level.”

For state legislation, Illinois could look to Minnesota and Montana for ideas. Both states had task forces that studied why Black women and girls and Native Americans (respectively) go missing and experience violence at higher rates than other races. Those task forces examined law enforcement disparities and shifted public funding toward community-led initiatives, in an effort to strengthen the public safety net and support impacted families.

This year Minnesota enacted legislation to create the nation’s first Office of Missing and Murdered Black Women and Girls with a $1.24 million annual budget allocation. The office will provide assistance with cold cases and offer grants to community groups to do prevention work around domestic violence and human trafficking, two issues which contribute to Black women and girls going missing. The office will set up public awareness campaigns and a missing persons alert system and serve as a point of contact for loved ones who do not feel comfortable speaking with police.

Montana’s task force led to the creation of the Montana Missing Indigenous Persons Reporting Portal, a project run by staff and students at Blackfeet Community College that is funded through a $25,000 Department of Justice grant. The portal supports Montana tribes in collecting better missing persons data and acts as a resource center — Native families can report their loved ones missing on the portal without interacting with law enforcement, and the project follows up on their behalf. The portal will also share information about missing loved ones on social media.

Another state initiative that Illinois could enact is regarding the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs). Illinois state law currently requires officials to tell families of missing people about the national database, which is used to centralize information and connect unidentified people across the nation. However, Illinois does not require law enforcement to input cases directly to NamUs — as Texas and 11 other states already do.

While this investigation found that individual officers have sometimes neglected or impeded missing person investigations, there are also current and former law enforcement officials — including some in leadership positions — who told reporters they want to see changes in the way the department handles these cases. These changes range from improving data collection to providing more resources for investigations and retraining officers for cultural sensitivity.

Police detectives are already operating with a high caseload and short staffing in the Special Victims Unit, as missing person cases are not a political priority within the department, sources say. “The police are expected to be everything. We’re supposed to be medics, family counselors, a bunch of other roles and then also the police,” says one current police officer, who asked to remain anonymous because he is not authorized to speak with the media.

“The most important thing for politicians is the safety of the city, and that means shootings. Everything else gets prioritized less than that because shootings are seen as the main danger to the city,” that same police officer says, and was echoed by other police sources.

One police source, a former missing persons detective, says detectives who are strapped for time often are left relying on phone calls, not in-person detective work, to parse through what’s happened in a case.

Commander Jason Moran of the Cook County Sheriff’s Office Missing Persons Project empathized with officers who become apathetic because they know the majority of missing people return or are located. He suggests to them, “Look at it from the standpoint of this missing person that’s been reported to you [who is] one of those bodies laying on a table down at the morgue.”

Moran requires his officers to verify in person that they have found a missing person before closing the case in order to prevent murdered women from going unidentified, leaving families without closure.

Part of the data collection issue seems to stem from internal confusion about how and when officers are allowed to mark a case “closed non-criminal.” Sources interviewed for this investigation, all with first-hand knowledge about this topic, contradicted each other in describing how missing person cases should be classified. For instance, one person said every single missing person case should be classified “non-criminal”; another said only cases resulting in murders should be classified “criminal.” CPD media affairs did not respond to a request for comment on its data practices.

Regardless of the department’s official or unofficial policies on classifying cases, many sources inside and outside CPD say the resulting data hurts the department’s ability to understand the missing persons problem and work toward solutions. In fact, national and state databases are built to allow updates to incident reports, using standardized language to describe which crimes have occurred, so that federal agencies can analyze crime trends.

Retired Commander Patricia Casey, who oversaw the juvenile missing persons desk from 2019 to 2021, advocated within CPD to collect more information on potential crimes that may occur while someone is missing.

“We wanted to make sure that there was a [sex] trafficking screening in there,” says Casey. She says the reform failed due to a lack of political will inside CPD headquarters, a sentiment echoed by other police sources who chose to remain anonymous.

Casey says that CPD should invest in a specialized missing persons unit where police “would investigate missings a lot deeper than we do now.” She believes that missing persons are not prioritized and detectives are spread thin in the Special Victims Unit, which covers domestic violence, youth who commit crime and missing persons. Nowadays, Casey continues her advocacy work as a member of the Chicago Missing Persons Guild, a group of volunteers who support impacted families and press state and city officials to improve how authorities handle missing person cases.

Casey is among multiple CPD sources who told reporters the missing person report is one of the last remaining incident reports done on paper. (Of these sources, four are currently employed at CPD and have asked to remain anonymous in order to avoid retaliation.)

All eight police sources say they believe switching to a digitized system (which is common at other large police departments, such as Miami and Washington, D.C.) would ensure that the data is collected and cases would reach detectives more quickly.

“It’s a much better system than having a paper process because with dealing with paper, it depends on how many hands it goes through; it can get lost,” says Commander Daniel Godin from the Youth and Family Services Division at the Washington, D.C., Metropolitan Police Department.

The Chicago Police Department declined to comment on why the missing person report has not been digitized, nor did they respond to questions about why officer arrival time is missing in thousands of cases.

In the “gender equity” plank of his election campaign, Mayor Brandon Johnson pledged to establish a missing persons initiative that would train civilians in trauma-informed crisis response.

“Our administration is committed to seeing these individuals and their families, investing in them, and providing the resources needed to solve these cases and bring justice and closure to loved ones and communities,” mayor’s office spokesperson Ronnie Reese says.

Johnson’s office did not respond to an interview request for more details on this plan, but directly funding community and family-led missing person searches in Chicago could bridge the gap in police services, says former Chicago Police Department homicide detective Gerald Hamilton, who in his retirement has supported searches for missing Black women and girls.

Community members are willing to do the work and support one another, he says, but they often lack training and resources — something a grant program could fix. “Today we are looking for your son and then tomorrow, we are looking for a member of the search party’s family,” he says. “It would set up community involvement.”

Latonya Moore, the mother of missing and murdered Shantieya Smith, agrees direct funding would alleviate the financial pressure on families and potentially bring people together. “It’s like taking back the block and building community when people are so distant,” she says.

Community groups in Chicago hope that city and state officials will similarly direct resources toward supporting families, providing services and building community spaces.

La’Keisha Gray-Sewell, the founder and executive director of Girls Like Me Project, a community group that provides support to Black teen girls in the Bronzeville area who are susceptible to exploitation and trafficking, believes safe houses are critical. “Before girls even go missing, I want it to be known that there are predators amongst us and that this should be a system in process whereby the community is keeping Black girls safe,” she explains.

“There should be a space where girls know that they can go, that this is a space that they won’t be in harm’s way,” she explains, adding it’s important for resources to exist outside law enforcement and the Department of Child and Family Services.

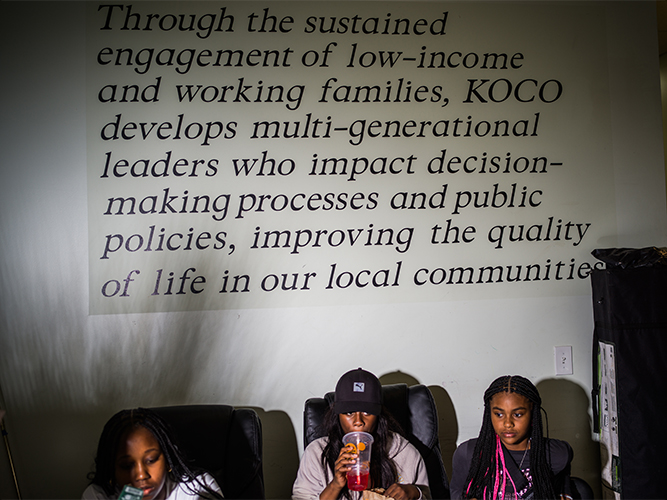

Regardless of what form future resources and initiatives take in Chicago, impacted families need a place at the table in creating solutions, says Shannon Bennett, executive director of the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization, which hosts the annual We Walk for Her march to raise awareness for the issue. “Victims and victims’ families need to be centered to bring recommendations,” he explains. “That’s why I’m leery of any recommendations coming in from people who haven’t had the lived experiences. Folks need to be centered in decision making and meaningful roles.”

Editor’s Note: